Reggio Emilia, a mid-sized city that sits roughly halfway between Milan and Bologna, is not your grandmother’s Italy.

For starters, it’s more hardscrabble than picturesque — heavily graffitied, with streets and buildings that feel weathered and worn from everyday use. And although you’ll still find the charming clock tower, the cobblestone streets and the Renaissance-era churches in the city center, you’ll also find a city in which one out of five residents is not from Italy itself, but places as far-flung as Ghana and Nigeria, Morocco and Albania, Yemen and Syria.

It is, in short, a microcosm of the changing face of Italy, and of the wider world: nascent, uprooted, and precariously perched between worlds and worldviews.

Why, then, is it also the home to the finest nursery schools in the world?

Recently, I traveled there to find out — along with more than 300 other educators from around the world. We were part of an international study group, scores of which regularly visit Reggio’s integrated public system of more than eighty infant/toddler and early childhood centers to bear witness to what has been created here — and wonder how it can be replicated elsewher

Because Reggio schools don’t exist anywhere else in the world — the closest you’ll find are schools that say they’re “Reggio-inspired” — they’re not well known outside of progressive education circles. But for those that do know, a visit to Reggio is akin to a pilgrimage to Mecca. And after spending five days there, walking the city’s streets, listening to lectures, and visiting several of its schools, I can see why.

Reggio Emilia is a city of altars — to childhood, to imagination, and to the spirit of shared governance and democratic participation. It is magical, but not in a precious way; it is revolutionary, but only because it has had the time and space to evolve; and it is illustrative, but not because it is prescriptive or straight-forward. In Reggio, the whole is always more that the sum of its parts. There are no shortcuts. And yet the path is as clear as can be.

To understand why, you must first travel back to 1945, when, after four years of worldwide war and two decades of domestic terrorism, a group of local residents made an unexpected (and unintended) discovery: one tank, six horses, and three trucks that were left behind by fleeing Nazi troops.

After some discussion, it became clear that by selling what they had found, the townspeople could underwrite an initial investment in their post-war future, and begin to write a new history in the wake of all that had been lost.

The men wanted to build a cinema. The women, a school.

Fortunately, the women won, and within weeks, the construction was underway. A young man named Loris Malaguzzi heard what was happening, and hopped on his bicycle to see for himself. “There were piles of sand and bricks,” he recalled, “a wheelbarrow full of hammers, shovels and hoes. Behind a curtain made of rugs to shield them from the sun, two women were hammering the old mortar off the bricks.

“We’re not crazy!” they exclaimed, unprompted. “If you really want to see, come on Saturday or Sunday, when we’re all here. We’re really going to make this school!”

For Malaguzzi, an elementary school teacher in a nearby town who would in time become the ceremonial leader of the the Reggio network, it was a life-changing moment. “It forced everything back to the beginning. It opened up completely new horizons of thought. I sensed that it was a formidable lesson of humanity and culture, which would generate other extraordinary events. All we needed to do was to follow the same path.”

The bedrock of that path was illuminated by a disturbing wartime lesson about humanity. “Mussolini and the fascists made us understand that obedient human beings are dangerous human beings,” he explained. “When we decided to build a new society after the war we understood that we needed to have schools in which children dared to think for themselves, and where children got the conditions for becoming active and critical citizens.”

Consequently, after seven decades of tinkering and revision, what a visitor will see in Reggio’s schools today are a series of design choices and principles that run counter to the way most of the world does ‘school.’

The goal is not knowledge; it’s communication

In Reggio schools, all adults believe that all children have at their disposal a hundred different languages — and that typically, “the school steals ninety-nine.” By languages, these adults do not mean merely the use of words, but also clay, paper, color, joy, imagination — anything that can help a child communicate his or her inner thoughts with the people around them. “We have not correctly legitimized a culture of childhood,” says Lella Gandini, a longtime Reggio teacher, “and the consequences are seen in all our social, economic, and political choices and investments.”

To counter this, Reggio’s schools are relentlessly child-centered — not to achieve notable results in literacy and numeracy, but to achieve notable qualities of identity formation and to ensure that all children know how to belong to a community. “Our approach offers children the opportunity to realize their ideas are different and that they hold a unique point of view,” said Gandini. “At the same time, children realize that the world is multiple and that other children can be discovered through a negotiation of ideas. Instead of interacting only through feelings and a sense of friendship, they discover how satisfying it is to exchange ideas and thereby transform their environment.”

I know, I know. It sounds amazing, but how do you actually teach that? What’s the curriculum in a Reggio school?

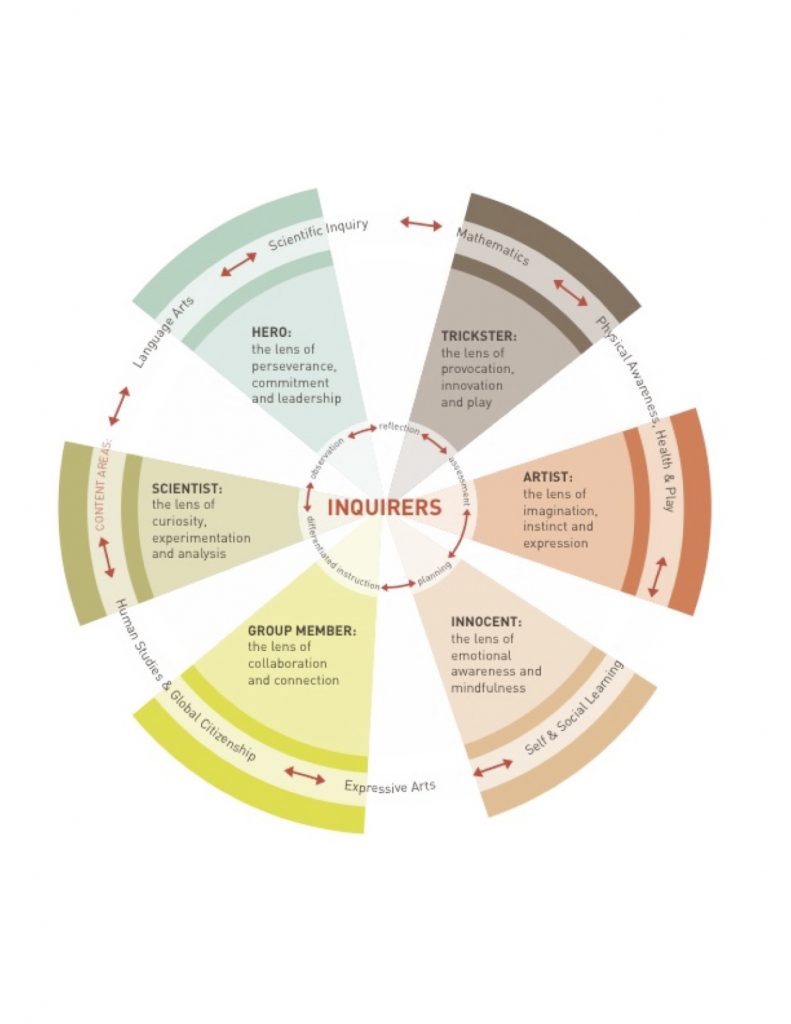

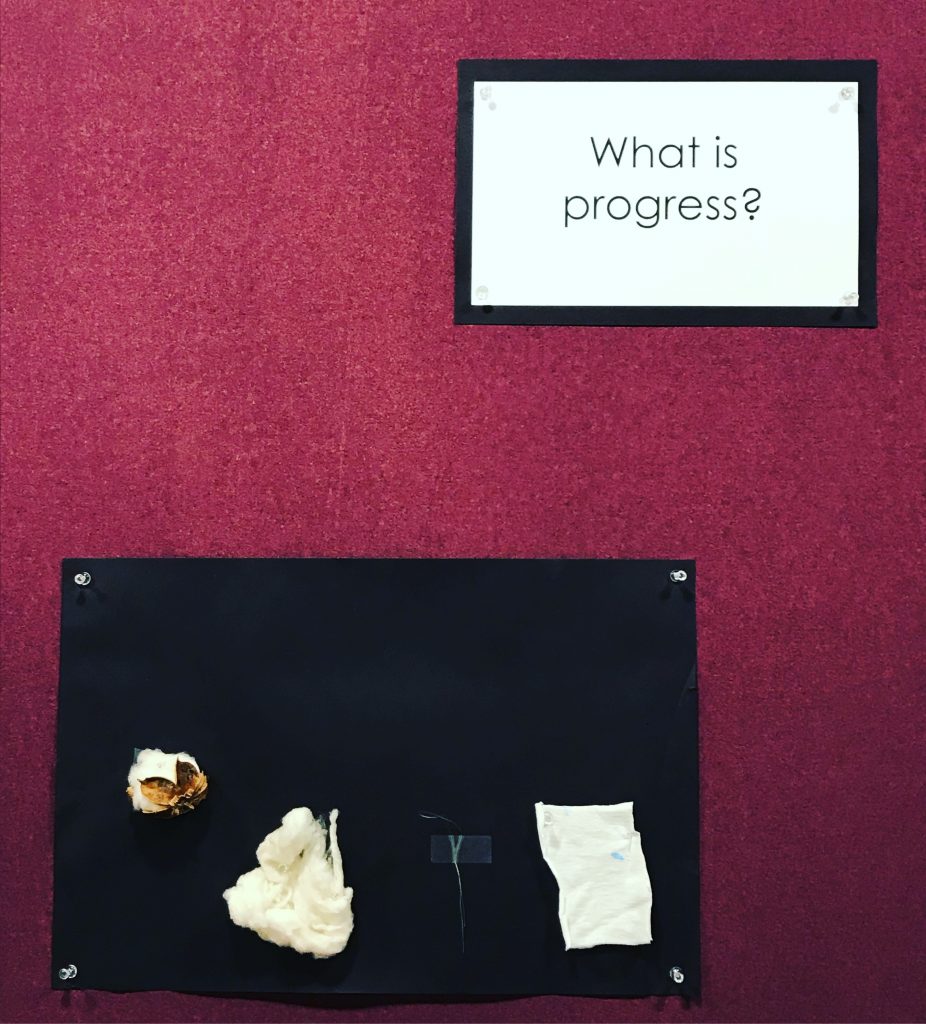

The curriculum is not fixed; it’s emergent

By design, Reggio schools were created to protect children from what Malaguzzi called the ‘prophetic pedagogy,’ or an education built on predetermined knowledge that got delivered bit by bit — a format Malaguzzi felt was humiliating for both teachers and children because of the ways it denied their ingenuity and emergent potential.

Consequently, Reggio teachers have no predetermined curricula (as the behaviorists would like), but neither do they work as constant improvisers. Instead, every year each school delineates a series of related projects, some short-range and some long. These themes serve as the main structural supports, but then, as Malaguzzi says, “it is up to the children, the course of events, and the teachers to determine whether the building turns out to be a hut on stilts or an apartment house or whatever. The teachers follow the children, not plans.”

To see this in action is part of what makes Reggio so magical, and the central feature it requires is a very different notion on the part of adults as to what their central role is, and is not. In this sense, teachers (and there are two in every classroom) are not there to deliver content, but to activate the meaning-making competencies of all children. As Malaguzzi put it, “they must try to capture the right moments, and then find the right approaches, for bringing together, into a fruitful dialogue, their meanings and interpretations with those of the children.”

Context, in other words, matters more than content. And the physical environment, after adults and peers, is the third teacher.

The space is not ancillary; it’s exalted

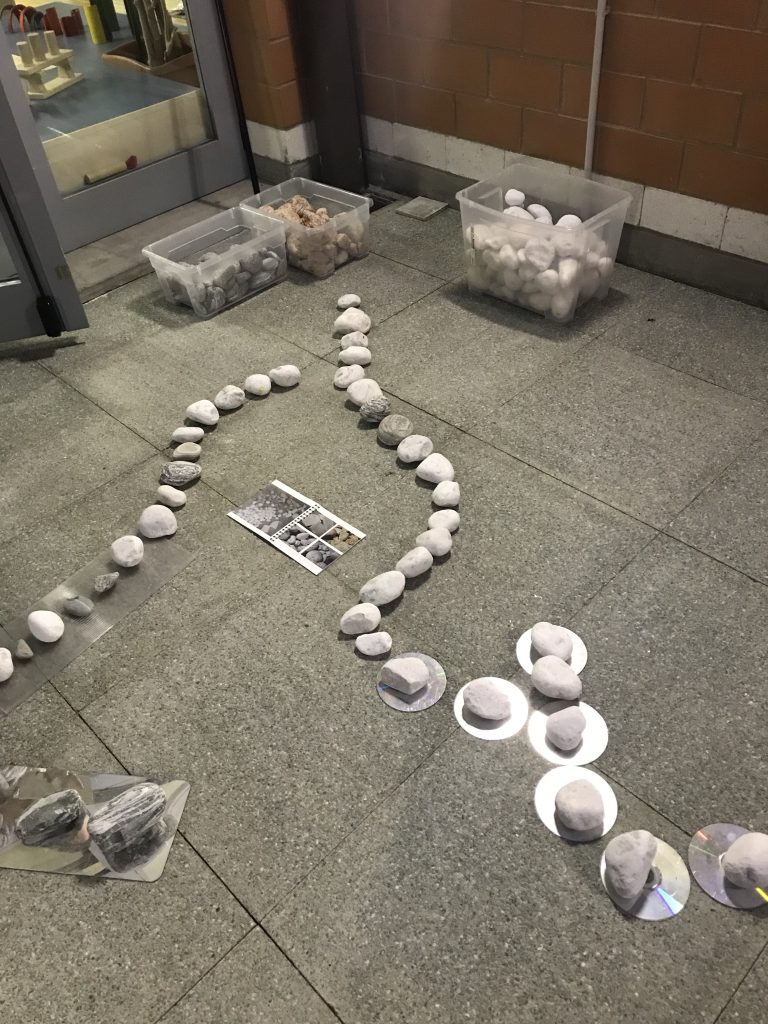

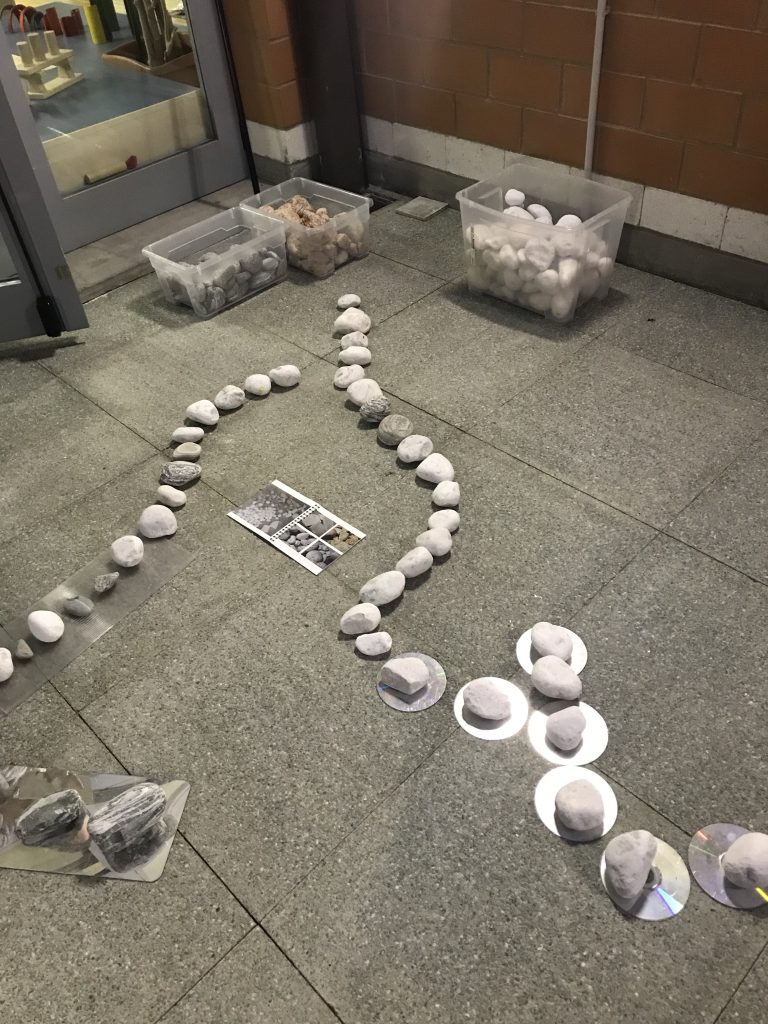

This is why every Reggio schools feels like a collection of altars. Great care is given to the construction of space, and to the conditions into which children will explore their hundred languages. Intricate patterns of stones snake through an outdoor courtyard, inviting children to continue the pattern, or to begin a new one. A bright orange slide cuts through thick stalks of bamboo, just because. The art materials are ubiquitous, and organized, and easily accessible. And the boundary between inside and outside is always as permeable as possible.

Here, the light is always able to come in.

It’s why Malaguzzi called the physical environment the Third Teacher. And it’s what led the celebrated psychologist Jerome Bruner to take particular note of a group of four-year-old children who were projecting shadows onto a wall on the day of his visit. “The concentration was absolute, but even more surprising was the freedom of exchange in expressing their imaginative ideas about what was making the shadows so odd, why they got smaller and swelled up or, as one child asked: “How does a shadow get to be upside down?” The teacher behaved as respectfully as if she had been dealing with Nobel Prize winners. Everyone was thinking out loud: “What do you mean by upside down?” asked another child.

It’s why Malaguzzi called the physical environment the Third Teacher. And it’s what led the celebrated psychologist Jerome Bruner to take particular note of a group of four-year-old children who were projecting shadows onto a wall on the day of his visit. “The concentration was absolute, but even more surprising was the freedom of exchange in expressing their imaginative ideas about what was making the shadows so odd, why they got smaller and swelled up or, as one child asked: “How does a shadow get to be upside down?” The teacher behaved as respectfully as if she had been dealing with Nobel Prize winners. Everyone was thinking out loud: “What do you mean by upside down?” asked another child.

“Here we were not dealing with individual imaginations working separately,” Bruner concluded. “We were collectively involved in what is probably the most human thing about human beings, what psychologists and primate experts now like to call ‘intersubjectivity,’ which means arriving at a mutual understanding of what others have in mind. It is probably the extreme flowering of our evolution as humanoids, without which our human culture could not have developed, and without which all our intentional attempts at teaching something would fail.”

The community is not apart; it’s integral

That sense of intersubjectivity is everywhere in Reggio Emilia; it is, in fact, the clearest measure of the school’s longitudinal success. As former mayor Graziano Delrio put it, “We in Reggio Emilia believe that we should manage our cities with the objective of building an equal community, acting for the common good of citizens to guarantee equal dignity and equal rights. We assert the right of children to education from birth. The child is therefore a competent citizen. He or she is competent in assuming responsibility for the city. I often quote this statement by John Adams, the second president of the United States: “Public happiness exists where citizens can take part responsibly for public good and public life. Everywhere, there are men, women, children, whether old or young, rich or poor, tall or short, wise or foolish . . . everyone is highly motivated by a desire of being seen, heard, considered, approved and respected by the people around him and known by him.”

Indeed, the success of Reggio schools would not have been sustained without meaningful partnership and support from its elected leaders. Today, almost 20% of the city’s budget goes towards its early childhood education programs. There is no neighborhood more desirable than another because of the schools; the system has equity throughout. Parents are integral to the success of each school, and play an active role in shared governance. And the spirit of civic participation here, in a city founded by the Romans in the second century B.C., and in a community that can trace its collectivist tendencies back to the craft guilds and communal republics of the medieval 14th century, is what led a mayor of an Industrial city in Northern Italy to proclaim that the infant-toddler centers are “public common spaces where the multitudes aim to become a community of people growing together with a strong sense of the future, a strong idea of participation, of living together, of taking care, one for others. The school expresses the society through which it is generated, but school is also able to generate a new society.”

The bedrock is not love; it’s respect

Finally, this.

It is easy to imagine that all we need to do is love children more, or give them more space, and the rest will take care of itself. But what I witnessed in Reggio was less a case of adults loving children — though surely, they did. Instead, what I witnessed was a level of listening, attention, and care that came from an unwavering belief that all children, even the newest among us, are social beings, predisposed, and possessing from birth a readiness to make significant ties with others, to communicate, and to find one’s place in the world of others.

“We think of school for young children as an integral living organism,” said Malaguzzi, “as a place of shared lives and relationships among many adults and many children. We think of school as a sort of construction in motion, continuously adjusting itself. Either a school is capable of continually transforming itself in response to children, or the school becomes something that goes around and around, remaining in the same spot.”

This is the path. These are the ingredients. But none of it is possible until, as the great theorist David Hawkins once said, we realize that “the more magic gift is not love, but respect for others as ends in themselves, as actual and potential artisans of their own learnings and doings, of their own lives, and thus uniquely contributing, in turn, to their learnings and doings.

“Respect for the young is not a passive, hands-off attitude. It invites our own offering of resources. It moves us toward the furtherance of their lives and thus, even, at times, toward remonstrance or intervention. Respect resembles love in its implicit aim of furtherance, but love without respect can blind and bind. Love is private and unbidden, whereas respect is implicit in all moral relations with others. Adults involved in the world of man and nature must bring that world with them to children, bounded and made safe to be sure, but not thereby losing its richness and promise of novelty.”

Amen.

To learn more about the Reggio Children Foundation, and/or to register for an International Study Group, visit https://www.reggiochildren.it/?lang=en

It’s why Malaguzzi called the physical environment the Third Teacher. And it’s what led the celebrated psychologist Jerome Bruner to take particular note of a group of four-year-old children who were projecting shadows onto a wall on the day of his visit. “The concentration was absolute, but even more surprising was the freedom of exchange in expressing their imaginative ideas about what was making the shadows so odd, why they got smaller and swelled up or, as one child asked: “How does a shadow get to be upside down?” The teacher behaved as respectfully as if she had been dealing with Nobel Prize winners. Everyone was thinking out loud: “What do you mean by upside down?” asked another child.

It’s why Malaguzzi called the physical environment the Third Teacher. And it’s what led the celebrated psychologist Jerome Bruner to take particular note of a group of four-year-old children who were projecting shadows onto a wall on the day of his visit. “The concentration was absolute, but even more surprising was the freedom of exchange in expressing their imaginative ideas about what was making the shadows so odd, why they got smaller and swelled up or, as one child asked: “How does a shadow get to be upside down?” The teacher behaved as respectfully as if she had been dealing with Nobel Prize winners. Everyone was thinking out loud: “What do you mean by upside down?” asked another child.

Recent Comments