Now the real work begins.

As this historic year (and election season) draws to a close, the barrage of warnings we have tried to wish away — spoken in the language of fires, floods, and invisible pathogens — make clear to anyone paying attention that the norms of the past are no longer tenable.

There can be no return to normal — because normal was the problem in the first place.

This is the hindsight of 2020.

To heed it, however, we must acknowledge how we got here — and then we must change our ways.

Consider this: whereas in 1500, we produced goods and services worth about $250 billion in today’s dollars, today it’s $60 trillion — a 240-fold increase. As a direct result of that conspicuous consumption, one-third of the Earth’s land is now severely degraded. There are half as many animals in the world today as there were in 1970. And we’ve used more energy and resources in the past thirty-five years than in the previous 200,000 — the total amount of time that homo sapiens have been alive and kicking.

Cultural anthropologist Wade Davis says these patterns of human behavior expose the fallacy that it was ever possible to achieve infinite growth on a finite planet. It is, he warns, “a form of slow collective suicide. To deny or exclude from the calculus of governance and economy the costs of violating the biological support systems of life is the logic of delusion.”

Yet we see evidence of our delusions in every direction.

In smoke-clogged Chinese cities, giant LED screens show daily videos of the sun rising.

In American schools and classrooms, it has become commonplace to have “active shooter” drills.

And people touch, swipe and caress their phones almost 3,000 times a day.

Against these odds, it’s easy to feel hopeless. And yet just as past behavior patterns have laid bare the extent of the damage we have done to the natural world (and ourselves), so, too, can our propensity as pattern recognizers lead us, in this first year of a Biden presidency and beyond, to course-correct in the service of a different story, and a different way of learning and living. As environmentalist Bill McKibben puts it, “the great advantage of the twenty-first century should be that we can learn from having lived through the failures of the twentieth. We’re able, as people were not a hundred years ago, to scratch some ideas off the list.”

What, then, are the ideas we should scratch off the list?

What should we start, stop and keep doing during the remainder of this pandemic-fueled pause from our regular routines?

And what, ultimately, is the shape of the change we seek — in our schools, our civic structures, and ourselves?

In a line worthy of a poet, Sir Ernest Shackleton remembered a similar moment of extreme shared trial: “Deep seemed the valleys,” he wrote, “when we lay between the reeling seas.”

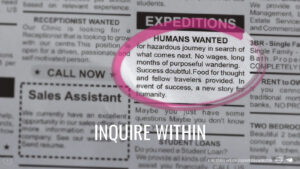

For Shackleton, the British explorer who, a century ago, placed an ad in which he sought 28 intrepid volunteers for a hazardous expedition to the Antarctic by promising “small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, and constant danger,” moving toward an uncertain future meant facing it with courage, belief, and imagination.

As 2020 (and this election season) draws to a close, we need a different expedition, and a different ad — not the exploration of a barren wilderness, but the effort to reclaim lost wisdom and ways of being, in the service of elevating a new story for the world.

HUMANS WANTED

For hazardous journey in search of what comes next. No wages, long months of purposeful wandering. Success doubtful. Food for thought and fellow travelers provided. In event of success, a new story for humanity.

The journey begins on 1.21.21. Will you be part of it?

Recent Comments