The story of us

What are you wondering about these days? What are you struggling with? What is becoming clear to you?

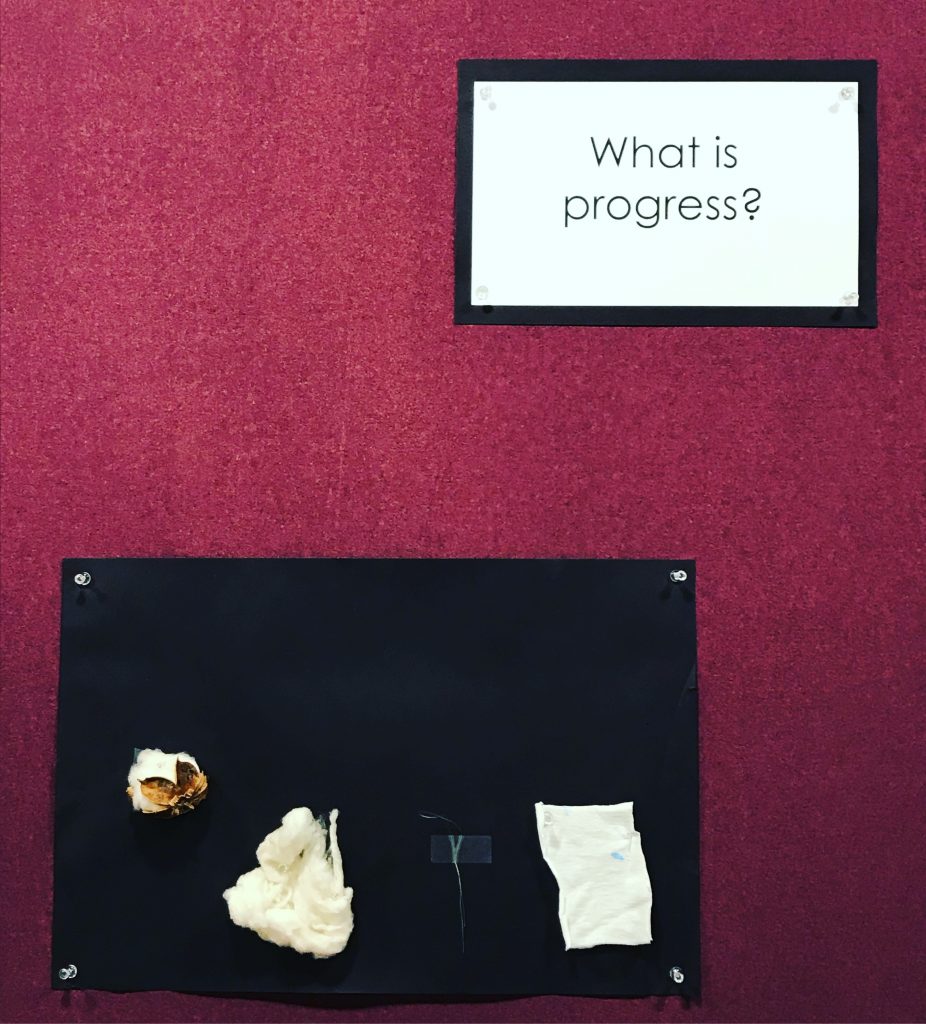

My answer to all of these questions relates to a new book we’re writing, and to our ongoing search to identify the irreducible elements of identity — the qualities and dispositions that we need in order to preserve, protect, defend, champion, encourage and honor the human spirit (and to do so at this exact moment of decadence, division, and decline).

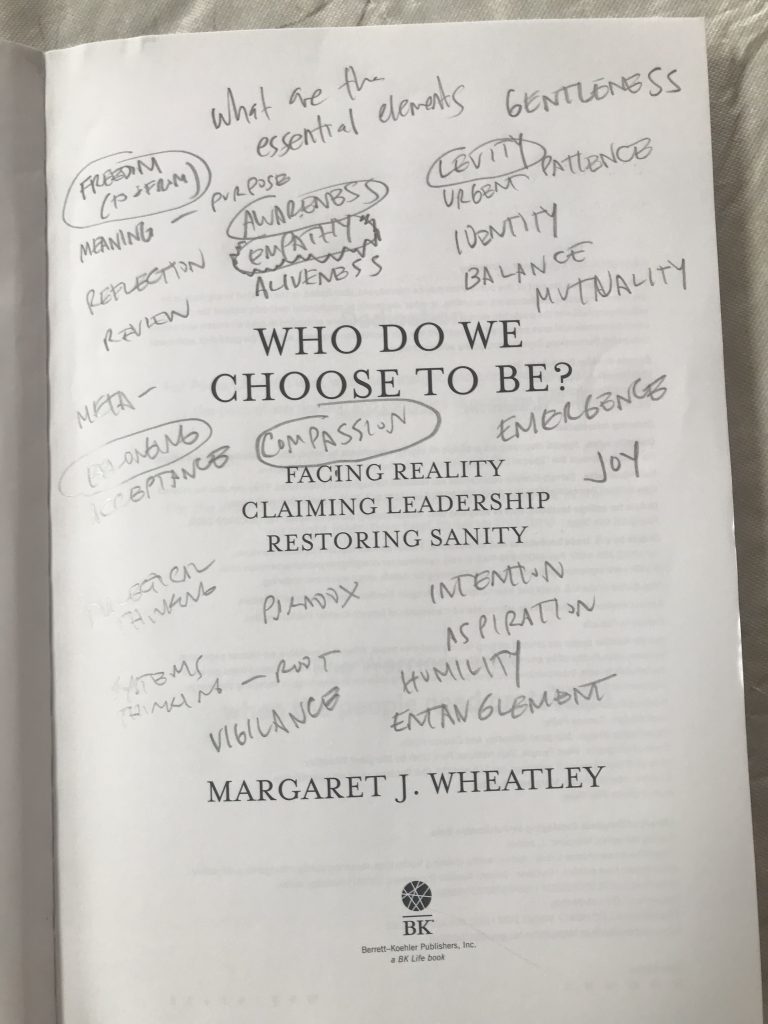

Towards that end, I just finished Margaret Wheatley’s new book, Who Do We Choose to Be (go read it!), and as I did, I jotted down some of the qualities that I think are element-al to our development of a healthy self and spirit.

I spend most of my waking hours in schools of the present that are working to recalibrate themselves into schools of the future. Across those experiences, I’ve observed some larger patterns to which we are all beholden:

The contours of global citizenship are shifting.

The barrier between man and machine is shrinking.

And the time it will take to undo the human damage to the natural world is running out.

Amidst so many uncertainties, what is the future path we must traverse? What will our students need to know, believe and do in order to add value to such a rapidly changing world? And how will our schools summon the professional courage to shift their practices in order to better support the personal growth of each new generation of young people?

This is the crux of our challenge. And I believe we won’t succeed until we retire the two dominant educational metaphors of the past one hundred years: the assembly line and the tabula rasa.

At best, they no longer serve us.

At worst, they actively prevent us from reimagining the structure and purpose of school.

The word metaphor combines two Greek words — meta, which means over and above, and pherein, to bear across. Metaphoric thinking is fundamental to our understanding of the world, because it is the only way in which understanding can reach outside the system of signs to life itself. It is what links language to life.

Consequently, a new era requires a new way of thinking. And based on what I have observed in some of the world’s leading schools and communities over the past two decades, these five metaphors for school (re)design feel like the right place to start:

For more than a century, we have unconsciously accepted an endless stream of assumptions about what school requires:

Subjects and departments.

Fixed curricula.

Grades.

Transcripts.

Credit Hours.

All of these structures have presupposed a fixed path for young people to follow.

For now, that path remains a viable one for many young people to pursue. Gaze a little further out, however, and you will see that the landscape is shifting — away from the notion of a singular path, and towards a much more elastic understanding of how each person can add value to the world.

This will require a new metaphor for how we think about the structure and purpose of school — away from the mechanistic notion of an assembly line, and towards something more emergent, inextricable, and alive.

Knowing this, how might we reimagine the spaces in which learning occurs so that the movement and flow of human bodies is closer to the improvisatory choreography of a murmuration of starlings than the tightly orchestrated machinery of a factory assembly line?

Indeed, what would a murmuration of student interest and passion look like in practice? What would it engender?

For too long, we have assumed that the purpose of a formal education was to arrive at a point of certainty about the world, and one’s place in it.

In the modern world, however, no one person or perspective can give us the answers we need. “Paradoxically,” as Margaret Wheatley has written, “we can only find those answers by admitting we don’t know. We have to be willing to let go of our certainty and expect ourselves to be confused for a time.

“It is very difficult to give up our certainties—our positions, our beliefs, our explanations. These help define us; they lie at the heart of our personal identity. Yet curiosity is what we need.”

Knowing this, how can we craft new experiences and learning spaces that will invite young people and adults to be more curious than certain — about themselves, one another, and the wider world?

Indeed, if the entirety of school was akin to a Wunderkammer — a cabinet of curiosities — how would our understanding of school need to shift?

In the past, the end-goal of schooling was to acquire a specific body of content knowledge. In the future, however, content will merely be the means by which we reach a more vital end-goal: a set of skills, habits and dispositions that can guide young people through life.

This shift is one that will require us to be in closer relationship with one another, for it is through others that we are made manifest in the world. It will require us to admire the beautiful question more than the elegant answer. And it will require us to focus more on the construction than the completion, and more on being present in the world than re-presenting it.

Knowing this, how can schools create the conditions that will allow for deeper learning expeditions that are less bound by space, time, and tidiness, and more by open-ended inquiry and discovery?

Indeed, instead of viewing school as a masterpiece we adults were waiting to deliver in finished form to our students, what if we understood it more as the chance to craft a partially-painted canvas — one that only the students themselves could complete?

One of the more curious features of human evolution is our bihemispheric brain.

In fact, our brains are designed to attend to the world in two completely different ways, and in so doing they bring two different worlds into being. In the one, as Iain McGilchrist has written, “we experience — the live, complex, embodied, world of individual, always unique beings, forever in flux, a net of interdependencies, forming and reforming wholes, a world in which we are deeply connected. In the other we ‘experience’ our experience in a special way: a ‘re-presented’ version of it, containing now static, separable, bounded, but essentially fragmented entities, grouped into classes, on which predictions can be based.

“These are not different ways of thinking about the world,” McGilchrist argues. “They are different ways of being in the world.”

This observation has clear implications for the future of school. If we know that the left hemisphere yields narrow, focused attention, while the right hemisphere yields a broad, vigilant attention, how might we more intentionally in our learning environments bring to bear both of these seemingly incompatible types of attention on the world in equal measure — one narrow, focused, and directed by our needs, and the other broad, open, and directed towards whatever else is going on in the world apart from ourselves?

This is the task of the brain — to put us in touch with whatever it is that exists apart from ourselves. And this, too, is the task of the future of school. How, then, might we envision our schools less as a series of separate departments, classes and cliques, and more as a holistic aspen grove — that biological marvel that appears at first to be an infinite forest of tall trees, but is in fact a single living organism (the oldest and largest on earth), bound together by a complex, interwoven underground root network?

Indeed, what does the concept of School-as-Aspen-Grove require us to design for, and prioritize, and be?

To understand the individual, we need to understand the environment in which they live. As Andreas Weber says, “we have to think of beings always as interbeings.”

To understand this principle in practice, consider the phenomenon of a swarm. Whether it be bees, or dolphins, or a school of fish, a swarm does not have intelligence; it is intelligence.

In a swarm, a huge connected whole arises from the local coherence of small parts. A swarm does not think. It is a thought process. And so in that sense, any swarm is an intensified counterpart of any individual self.

Knowing this, in what ways can we craft spaces and experiences that invite young people (and adults) into this sort of synchrony?

Indeed, how do we unlock the school-based choreography, and the collective intelligence, of a swarm?

The good news is that this work is not merely an abstract set of concepts. In fact, it’s already well underway, providing us with myriad examples of what these metaphors look like in practice — from the school-as-murmuration model of Crosstown High in Memphis to the Aspen-Grove-integration of the Brightworks School in San Francisco, or from the hundreds of partially-painted-canvas schools in the Big Picture Learning network to your neighborhood Montessori school, whose close attention to the nexus between the materials children use — their cabinet of curiosities — and the way they feel about learning can be witnessed in nearly 25,000 different environments around the world.

In other words, the previous era of thinking is over.

A new era has begun.

Watch this video. What do you see?

Literally, of course, it’s a sacred cow. And what strikes me is how everyone around it unconsciously adjusts what they do, to the point that the cow has become all but invisible to the chaos of a morning commute — and how ridiculous that is.

We have sacred cows here, too — but whereas in Nepal they literally block traffic, in America they block our ability to think in new ways. And I can think of no aspect of our shared public life with more sacred cows than America’s schools:

Grades. Bells. Schedules. Credit Hours. Classrooms. Tests. Transcripts. Homework. 180 days. Age-based cohorts.

And the list could go on.

For that reason, 180 Studio and ATTN are partnering on a new series, Ask Why, that is designed to help us reflect on a fundamental question:

How should we continue to think about the structure and purpose of public education? Which rituals and habits from our collective past should we hold onto — and which should we let go of in order to reimagine teaching and learning for a rapidly changing world?

So stay tuned for the first few episodes in the series — and keep your eyes open for sacred cows. They’re everywhere.

Is it possible for people to change the story we tell ourselves (and one another) about public education?

I spend a lot of time thinking about this question. And some recent studies all suggest that if the answer is ever going to be “yes,” we have some serious work to do.

Consider the work of cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber, whose book The Enigma of Reason demonstrates why facts don’t change our minds. In study after study, they have shown people overwhelming evidence to refute a deeply held belief, and then watch as those same people “fail to make appropriate revisions in those beliefs.”

How does this play out in modern life? In Science Speak it’s known as the “illusion of explanatory depth,” which basically means that we all believe we know way more than we actually do. And what is it that allows us to persist in this belief? Other people, so much so that on almost any issue of significance, we can hardly tell where our own understanding ends and others’ begins.

So what does any of this have to do with changing the story about public education?

At first blush, nothing.

But when you start to think of the extent to which our public school system has been shared by a group of animals that are evolutionarily wired to reinforce the same way of thinking and feeling about things, you start to appreciate just how powerfully the memes we have about teaching and learning continue to shape, and hinder, our collective capacity to imagine new ways of addressing old problems or institutions.

Memes get talked about a lot these days as catchy GIF files on Instagram, but before they were that, they were the ideas or memories that get shared among people in a given culture. And because they’re so widely experienced — and so ubiquitous in the American public school system — memes are powerful obstacles to change.

As Geoffrey and Renate Caine make clear in their book Natural Learning for a Connected World: “Traditional education is driven by a powerful meme that keeps replicating itself. One simply has to imagine several people gathering to talk about education to recognize how powerfully the meme is embedded. Individuals will visualize desks and books and a teacher in the front of the classroom. Grades, tests, discipline, and hard work will bind together the beliefs that everyone automatically subscribes to. These beliefs linger as foundational ideas that are rarely, if ever, questioned.”

Because we have such a strong shared sense of what schooling is (and isn’t), even small-scale changes to the way we think about public education will be likely to spark large-scale resistance. And yet rarely, if ever, do you hear a discussion of memes make its way into the national debate about school reform. It’s the equivalent of trying to help a garden grow by removing all the visible weeds — and ignoring all the invisible root structures.

In other words, well-reasoned arguments for or against the educational benefits of (fill in the blank) are not the way forward, because they only represent one part of the picture. Far more influential are the social and emotional memories we bring to the idea of elementary school itself, or the level of individuality we ascribe to our own memories of high school, or the extent to which we fear the prospect of replacing something familiar with something unknown.

Consequently, when it comes to changing the story about public education, there is only one conclusion to draw from the research: We have met the enemy. And it is us.

At its best, nothing is more unifying and vital to a community’s civic health than a high-quality neighborhood school. Why, then, do all notions of “school choice” end up being about either charter or private schools?

Enter Oakland SOL, a new dual-immersion middle school in the Flatlands section of Oakland, California — and the district’s first new school in more than a decade.

Created over three years of hard work and careful planning by a motivated group of local parents and educators, Oakland SOL paints a different picture of school choice — one that is squarely grounded in the aspirations of the families and children who will comprise its community core.

To some, it’s a murky picture. After all, Oakland’s school district already has more schools than it can afford; it faces up to a $30 million budget shortfall. Yet when you consider that after fifth grade, one of every four students in the district leaves the system, Superintendent Kyla Johnson-Trammel is making a different sort of bet — one that will require districts to become more responsive to local needs and demands.

“If we can provide programs that help them make the choice to stay in our district, I actually do think that’s fiscally responsible,” said Katherine Carter, SOL’s founding principal. “It shows the district cares about creating quality experiences for our kids and our families.”

“This was really rooted in parent demand,” added Gloria Lee, president and chief executive of a local nonprofit that supports new public school options. “I hope it is the first and not the only example of a way the district can continue to evolve and create new innovative programs that serve the really diverse families in Oakland more effectively.”

We know more than we think we do.

Now is the time for a new learning story.

#thisis180

For more than a century, the physical layout of American schools has been as consistent as any feature in American public life. Although the world around us has been in a constant state of flux, we have always been able to depend on a familiar set of symbols in our schools: neat, orderly rows of student desks; teachers delivering lessons to an entire group of children; lockers in the hallways; bell schedules — the list could go on.

But what if those timeworn structures of schooling are actually preventing us from modernizing education for a changing world? What if, in fact, the physical environment is — after parents and peers — the “third teacher” of our sons and daughters?

The latest short film in our multimedia story series about the future of learning, 180: Thrive provides a window into one school’s efforts to directly tackle those questions, and do so in a way that results in a deeper alignment between what we know about how people learn — actively, collaboratively, differently — and how our schools are physically structured. It is intended to spark useful broader thinking about the relationship between a school’s physical environment and its students’ emotional readiness to learn.

This is how we reimagine learning.

This is how we #changethestory.

#Thisis180

Of our fifty states, I can think of no other whose local history — for better and for worse — captures the essence of the larger American story.

In a sense, we are all Mississippians.

To wit, our next 180 story provides a glimpse of the systemic and generational impacts of racism, and how vital investment in education is to all residents — and to the entire state’s economy. We see this all through the eyes of local organizer (and Mississippi native) Albert Sykes, his 11-year-old son Aidan, mothers in Jackson Public Schools, a mayor, a school board member, and other community advocates. Part history, part vignette, and full of humanity, our hope is that Mississippi Rising will begin to connect the dots of who needs to be engaged to identify, understand, and create a bright future for Mississippi that involves the entire community.

The release of this video is timely. On September 14th of this year, the Mississippi State Board of Education recommended a state takeover of Jackson Public Schools. Governor Phil Bryant is considering the recommendation, while many of Jackson’s students, families, faith, and business leaders — along with the Mayor of Jackson and several school board members — believe they should be the ones to determine the future of Jackson Public Schools. They are asking the Governor to support local governance. Commenting on the Governor’s decision, says Albert Sykes, the Executive Director of IDEA, “The Governor – and even the State Board – may have the right concern, but a takeover of JPS is clearly the wrong policy.”

The Breadcrumbs: Additional vignettes and calls-to-action (CTAs)

#myJPS is a video featuring the student voices naming the future they want for Jackson Public Schools.

#OurJPS is the group leading local organizing efforts on the ground.

Must read: State takeovers of low-performing schools – a 2016 report from the Center for Popular Democracy examines the record of state takeovers of districts in three other states.

Additional background on the takeover being considered in Jackson and a petition that was created to stop the takeover by JPS School Board Member Jed Oppenheim – who is shown in Mississippi Rising.

Georgia faced a statewide takeover of its public schools one year ago – and the people of Georgia made clear they wanted community-driven strong public schools.

Learn more about the Algebra Project.

Implicit bias doesn’t just play out in classrooms. The schools, states, and districts where a “takeover” approach to school change has been deployed are disproportionately attended by students of color. Here’s a podcast from the Communities for Just Schools Fund on implicit bias.

Register for this October 25th webinar to learn more about effective organizing for strong racially just public schools and communities.

Thank you for watching. And stay tuned! #thisis180

One year, early in my teaching career, I got reprimanded for giving too many “A’s.”

“You can’t give everyone the same grade,” I was instructed. “Give a few A’s and F’s, and a lot of B’s and C’s. Otherwise, everyone will know that your class is either too easy or too hard.”

This was unremarkable advice; indeed, it was as close to the educational Gospel as you could find. It was human nature in action.

And, apparently, it was completely wrong.

“We have all come to believe that the average is a reliable index of normality,” writes Todd Rose, a professor at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education and the author of The End of Average: How We Succeed in a World That Values Sameness. “We have also come to believe that an individual’s rank on narrow metrics of achievement can be used to judge their talent. These two ideas serve as the organizing principles behind our current system of education.”

And yet, Rose suggests, “when it comes to understanding individuals, the average is most likely to give incorrect and misleading results.”

In fact, the origins of what Rose calls “averagarian thinking” had nothing to do with people; they were adaptations of a core method in astronomy — the Method of Averages, in which you aggregate different measurements of the speed of an object to better determine its true value — that first got applied to the study of people in the early 19th century.

Since then, however, this misguided use of statistics — by definition, the mathematics of “static” values — has reduced the whims and caprices of human behavior to predictable patterns in ways that have proven almost impossible to resist.

Consider the ways it shaped the advice I got as a teacher, which was to let the Bell Curve, not the uniqueness of my students, be my guide. Or consider the ways it has shaped the entire system of American public education in the Industrial Era — an influence best summed up by one of its chief architects, Frederick Winslow Taylor, whose applications of scientific management to the classroom gave birth to everything from bells to age-based cohorts to the industrial efficiency of the typical school lunchroom. “In the past,” Taylor said, “the man was first. In the future, the system must be first.”

Uh, yeah. No.

Of course, anyone who is paying attention knows that the end of the Taylorian line of thinking is upon us — and Rose’s book is but one of the many factors that will expedite its demise. “We are on the brink of a new way of seeing the world,” he predicts, and “a change driven by one big idea: individuality matters.”

In systems thinking, there’s a word for this approach: equifinality — or the idea that in any multidimensional system that involves changes over time, there are always multiple pathways to get from point A to point B. And the good news is that this revolution in thinking is already underway – it’s not just evenly distributed.

The bad news is that most of us have no idea that a revolution is occurring. Instead, we are stuck in the familiar notion that most American schools are failing, that the problems are too big to tackle, and that our slow and steady decline into, well, averagarianism, is inexorable.

I am here to tell you this is not true.

We know more than we think we do.

We are further along than we think we are.

And so, in the coming months – approximately every ten days for the foreseeable future – expect a new story that is about solutions, possibility, and the people and communities whose work is lighting that new path.

The Age of the Individual is upon us.

#thisis180

As an educator, I can’t think of a more important, elusive, and agonizing question than this doozy: How do you measure success?

So you can imagine my surprise when I discovered a new source of inspiration for how we should answer it, by way of a 27,000-acre fish farm at the tip of the Guadalquivir river in Southern Spain.

The farm, Veta La Palma, is led by a biologist named Miguel Medialdea. I learned about Miguel’s work from a 2010 TED Talk by renowned chef Dan Barber, who first became aware of Miguel after discovering just how unsustainable “sustainable fish farming” practices really were.

To produce just one pound of farm-raised tuna, for example, requires fifteen pounds of wild fish to feed it. Nothing sustainable about that. In response, industry leaders have dramatically reduced their “feed conversion ratio” by feeding their fish, well, chicken – or, more specifically, chicken feathers, skin, bone meal and scraps, dried and processed into feed.

“What’s sustainable about feeding chicken to fish?” Barber asks his audience, to peals of laughter. Yet there’s nothing funny about the ways we have decimated the large fish populations of the world. And there’s nothing funny about an agribusiness model that, in an effort to find ways to feed more people more cheaply, has in fact been more about the business of liquidation than the business of sustainability.

Enter Veta La Palma, formerly a cattle farm, and now a sprawling series of flooded canals, flourishing wildlife, and fecund marshland. In fact, because it’s such a rich system, Veta La Palma’s fish eat what they’d be eating in the wild. “The system is so healthy,” Barber explains, “it’s totally self-renewing. There is no feed.

“Ever heard of a farm that doesn’t feed its animals?”

Eventually, Barber asked his host the $64,000 question: how they measure success. Medialdea pointed to the pink bellies of a thriving population of flamingos.

“But Miguel,” Barber asked, “isn’t a thriving bird population like the last thing you would want on a fish farm?”

“No,” he answered. “We farm extensively, not intensively. This is an ecological network. The flamingos eat the shrimp. The shrimp eat the phytoplankton. The pinker the belly, the better the system.”

It was at this point I thought about how much of Miguel’s work had lessons for our own.

Like agribusiness, education has been shaped by the logic of a single question for as long as anyone can remember. Indeed, just as feeding more people more efficiently has led us into a feedback loop in which we constantly erode our own global supply of fish, educating more children more efficiently has yielded a shell game of metrics that have allowed us to falsely claim success (or failure), when in fact all we have been doing is eroding a different, more precious supply: our ability to fall in love with ideas.

You know this, but it’s worth saying again: the ultimate measures of success in our schools cannot be reading and math scores, or better attendance, or higher graduation rates (though those are all good things). These are not our Pink Flamingos, because they are not indicative of a thriving ecology in our schools.

At Veta La Palma, the best way to measure the system’s overall quality is by gauging the health of its predators. What is the equivalent measure in our schools? If we started to view our schools less as solitary islands, and more as single links in a systemic chain of each child’s growth and development, how would we measure success then? What would we need to start, stop and keep doing?

For starters, I think we’d want to track every available measure of that child’s overall health: mental, nutritional, social, emotional, developmental – and yes, intellectual. We’d stop assuming that schools are capable of being assessed in a vacuum, and start making sense of their effectiveness amidst a larger network of institutions and services (think how much this would change the perception of private schools). And we’d keep looking at existing efforts to apply a more ecological approach to learning, from the Community Schools model, to instruments that help measure a child’s sense of hope, engagement and well-being, to individual schools that proactively measure – wait for it – curiosity and wonder, to, yes, the nearly 22,000 Montessori schools around the world.

These priorities would also lead to a different set of questions that could drive future innovations:

To transform sustainable farming, Dan Barber proposed a new question: “How can we create conditions that enable every community to feed itself?

The same lessons of scale are true for sustainable schooling. As Miguel Medialdea puts it, “I’m not an expert in fish; I’m an expert in relationships.”

So are America’s educators. The central goal of schooling is not to instill knowledge, but to unleash human potential. The central model for schooling is not a factory; it’s an ecosystem. And the central measure of success is not a single benchmark, but a comprehensive ability to affirm the overall health of the systems that surround our children as they learn and grow.

So let’s get serious about applying two billion years’ worth of proof points in order to build, and measure, the ecological networks our kids actually need in order to learn and grow. It’s the only way to find the Pink Flamingos that have eluded us thus far.

Recent Comments